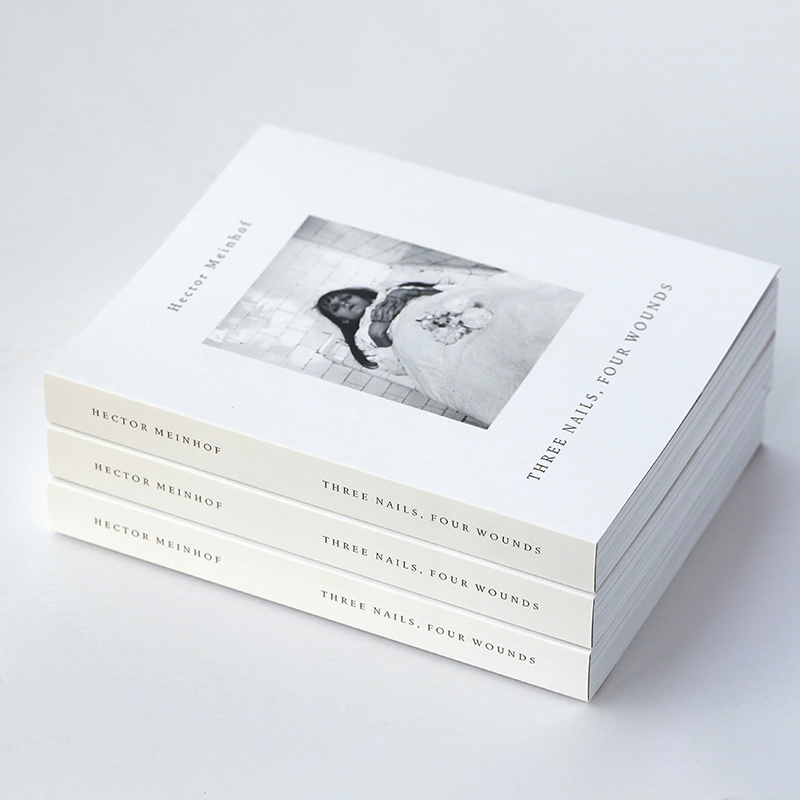

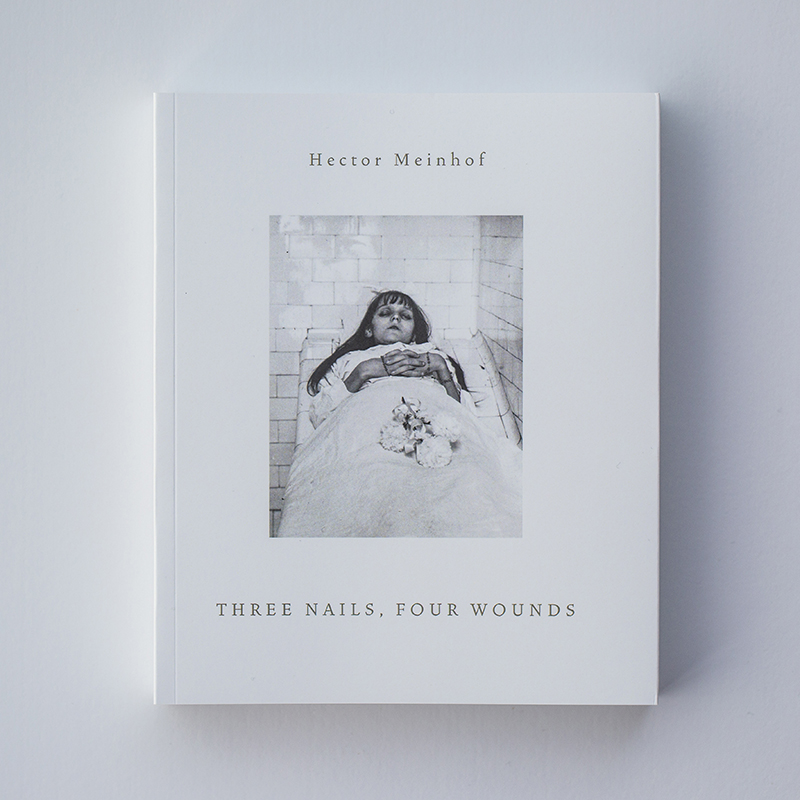

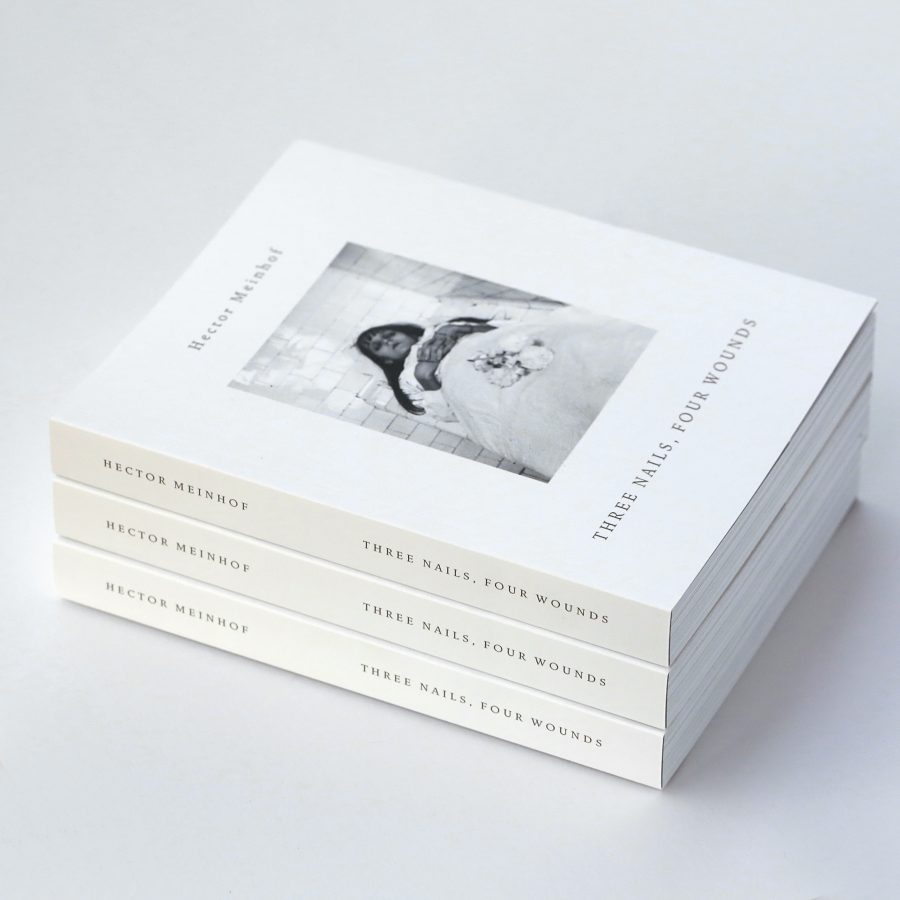

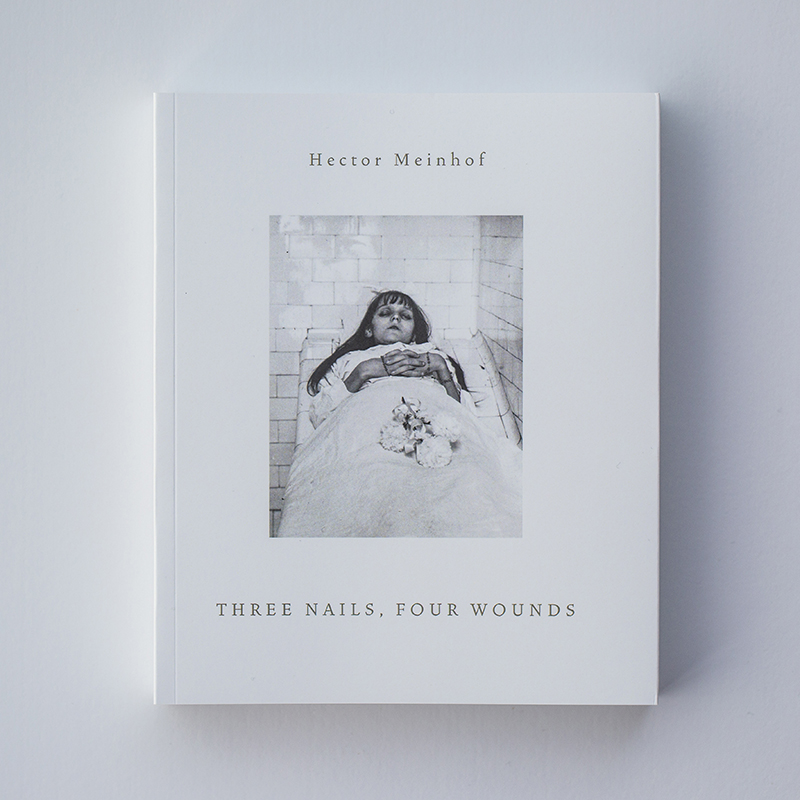

Hector Meinhof is an author and musician out of Sweden that has recently released his debut book, Three Nails, Four Wounds through Infinity Land Press. Outside his writing, Meinhof is known for his work as a classically-trained percussionist. He’s performed as part of Kroumata, a percussion ensemble. He’s also part of the scenic music duo, Hidden Mother. He is a collector of antique photography, specialized in post-mortem, medical and religious themes.

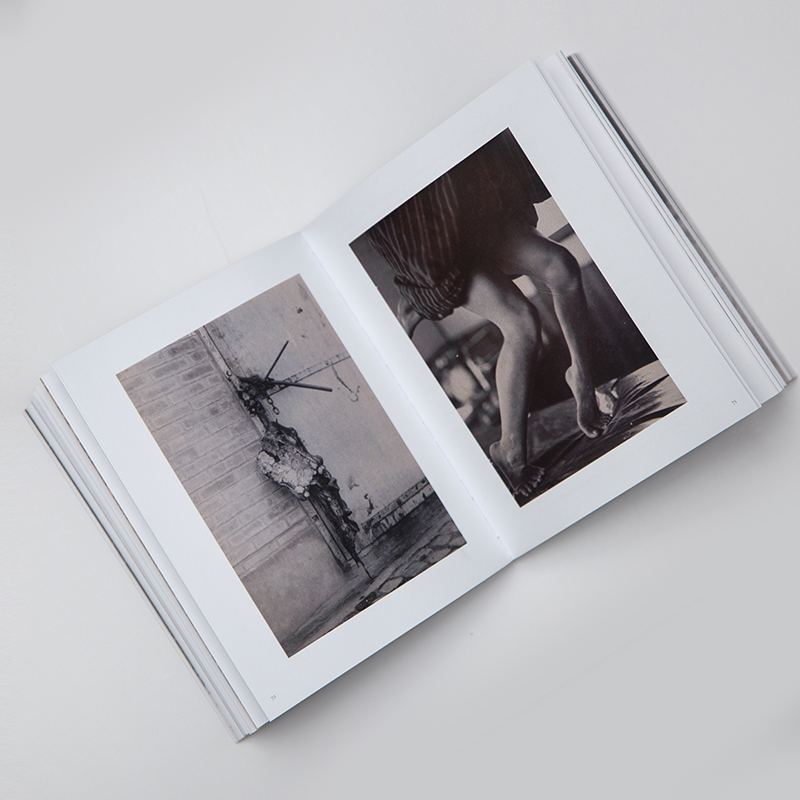

This book had a real impact on me, more so than with many/most books I’ve read in recent years. There is a perfect melange of macabre photography with a strange story that takes place in an asylum, centered on seven 11 year old girls. The story is filled with brilliant allusions to an apocalypse, mental/physical disability, old-fashion asylum conditions, and a dark and twisted conception of Christianity. Mingled with this is a very unique writing style, a blend of dialogues, poetry, and prose which all come together with the images to form an incredibly powerful experience.

Hector Meinhof has written a book that is both beautiful and cruel. His poetic prose and the doom-laden pictures from his extensive collection of vintage photographs have bled into one tortured, corporeal unity. This is the illustrated scripture for the new dark ages, it will be read and beheld again and again. – Martin Bladh

I decided that only reviewing the book wouldn’t do this work enough justice. I wanted to delve into the topics a bit deeper with Meinhof and find out a bit more about this promising new artist to the literary world. There will be a review coming along soon, but for now I highly recommend this book! Enjoy, and thank you all for your continued support of This Is Darkness and the works we cover!

Interviewee: Hector Meinhof

Conducted by: Michael Barnett

Michael: First off, thank you very much for agreeing to the interview. Three Nails, Four Wounds was my first introduction to your art-form and I must say I am incredibly impressed. I rarely am eager to go right back to the beginning of a book and start reading again, immediately after finishing it. But this the case with Three Nails, Four Wounds.

Hector: Thank you for those kind words, Michael. I’m looking forward to hearing your questions. Let’s dig into it!

Michael: Christianity plays a major role throughout the narrative of Three Nails, Four Wounds. What is your particular relationship with religion? Do you fascinate on it from afar, or do you hold some beliefs?

Hector: I did not have a religious upbringing at all (by the way: Sweden is mostly protestant). I thought religion was the most boring subject when I went to school. I didn’t care about these things until my 30s when I started to read about Christian mysticism. People on the fringe of society have always interested me and all those eccentric mystics – the saints, the stigmatics, Christ-erotics, those crazy nose-bleeding nuns, levitating, fasting, suffering, flagellating themselves – really struck me as the most extreme way of life ever recorded in the human history. It also made me aware of my Christian heritage. In the West – especially in Europe – we are all cultural Christians whether we like it or not. It’s not just the architecture, music, art, philosophy – but it’s in our way of thinking, in how we perceive things. So, whether you believe Christ was crucified for our sins or that he was “incompetence hanging on a tree” [Anton Szandor LaVey] it doesn’t really matter – we are what we are because of Christianity. In Scandinavia, Christendom is of course mixed with Norse mythology (look at the Norwegian stave churches with their dragons). Personally, I don’t have a problem with our Christian heritage, it has given birth to astonishing art, literature and philosophy, a rich set-up of archetypes that can guide and inspire, and the church’s demand for control wasn’t strong enough to keep the light of science from creeping in.

Michael: Martin has mentioned in the Afterword that it took you a great deal of time to find your individual writing voice. Do you think you’ve finally found that voice with Three Nails, Four Wounds?

Hector: That’s a good question. There are so many books in the world – is it even possible to create something new? Since I can’t do better work than Dante, Göthe, Shakespeare, Bronte, Dostoevsky, Huysmans, Rilke, Woolf, Proust, Camus, Bataille, Zürn, Ungar and Wittkop, already have done, I need to find themes, or a combination of themes, that haven’t been explored (at least not the way I do it); combine that with a personal style regarding language and form – then maybe you can create something that at least could be perceived as original. I had been writing for many years, but never thought anything turned out good enough for publishing. This time I thought it did. I guess this is my voice then – but I suspect that it will change over time. It took a long time for me to learn how to write, let’s leave it at that.

Let me add that when I started to write “Three Nails, Four Wounds” I knew that I wanted the story to take place in a hospital, and that although the religious themes would be there (like a skeleton of the book), my main focus was to find ways to express feelings of despair, pain, loneliness, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, a frustrated stutterer full of things to say lacking the ability to talk freely, and mental illness in general. I didn’t want it to be a conventional novel (building up characters, etc.), and I wanted a slightly surreal tone in the girls’ speech – that was my biggest problem: how to make them talk like they were from another dimension of life. So, I got the idea of using old poems (written ca. 15 years ago) as lines – and that’s how I found the tone in the dialogue. At one stage, I did consider composing the book entirely of lines of dialogue, but it felt too constructed.

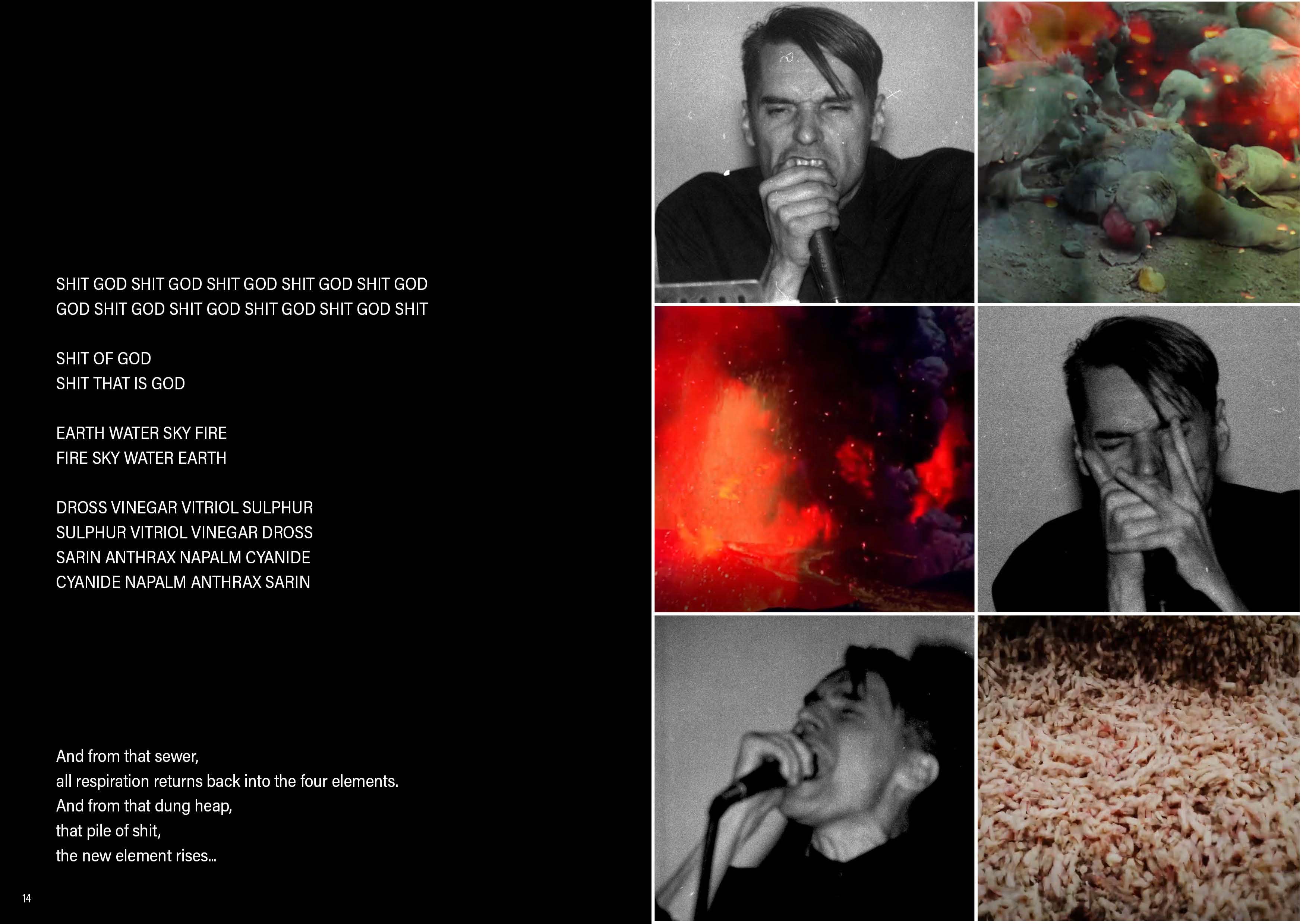

From Three Nails, Four Wounds

Michael: Was Three Nails, Four Wounds part of this process of finding your voice, or did you begin the book after you felt that you were in this proper mindset and had found a narrative voice suitable to continue with a more intensified and directed focus?

Hector: I guess “Three Nails” was part of the process. I wrote the book, read it, and felt for the first time that this book made it through the needle eye of my ambitions. I was ready. Twenty years from now, I will hopefully be a much better writer and then I will probably see flaws in this first book of mine – but I do believe that I will stand behind it and defend it.

Michael: Would you like to elaborate on some of the ideas that you were working on when writing this book?

Hector: My heroines, the seven 11-year-old girls, are not victims of anything, they act without hesitation, they are not afraid of the present. And many people are afraid of the present. A psychologist (I can’t remember who) talked about a man, happily married with children for 15 years. One day, his wife tells him that she has had an affair for the last five years and that she wants a divorce. The man is shocked. He says: “But I thought we were happy – when we had dinner last weekend, our holidays in France, when we visited your parents… Now, it’s like I don’t know myself anymore” – and the man had a breakdown. Happy memories turned into memories of deceit. His wife’s betrayal had changed his past, his history. So, the present can change the past, and that’s why it’s scary. In the present, we lack control. Everyday unexpected things can happen. Someone might walk up to you and say or do something that changes your past – and then we don’t know who we are anymore. The seven 11-year-old girls don’t remember, maybe they don’t have a past at all – and they are not afraid of anything.

My heroines are female because I think Woman has a certain inclination to spirituality – and most important: they use their body to express this spirituality. Reading about, for example, Mechthild von Magdeburg (which is quoted in the book), there is a very physical side to her belief in God. She talks about Christ more as a physical lover rather than something unreachable. The female saints bleed, they experience stigmata, they fast, they throw up objects, they levitate; when their bodies are dead they smell of flowers, when their hearts are dissected we find patterns and symbols inside. It seems to me, that female mystics use their flesh in a way male mystics don’t (there are, of course, exceptions). Their worship is like an art-form – and makes me think of contemporary performance artists, such as Marina Abramovic, especially her work in the 1970s.

Editor’s Note: An interesting article, if you want to learn more about some of Marina Abramovic’s work in the 70s.

https://www.elitereaders.com/performance-artist-marina-abramovic-social-experiment/?cn-reloaded=1

Hector: My heroines are children because I wanted them to be virgins. You could say that I use the seven 11-year-old girls as a cliché of the innocent childhood, not yet affected by social rules, sensual not sexual etc. But there’s a deeper meaning to it: their virginality – and I’m not talking about the bodily aspect of the term, but rather as a mental state. The virgin is self-enclosed, remote, secluded, turned inwards, doesn’t please others, penetrating only her own body, sterile, uncontaminated. Virginity as a state of mind is a sort of resistance. Let me quote from a book I just read [Images of the Untouched, 1982] about how to make a unicorn trap. You place the virgin in a forest, “with her breast uncovered, and by its scent the unicorn perceives it; then it comes to the virgin and kisses her breast, falls asleep on her lap and so comes to its death.” You could interpret the unicorn as “the spirit”, and the ”unicorn trap” as a way to unite the spirit with the body. “The virginal nourishes the spirit, while spirit makes the virginal psyche pregnant.” So, virginity as a state of mind is to be pregnant – that is: creative. In some cultures, the menstrual blood is viewed as a manifestation of creative power, especially a girl’s first menstruation. So, in my book you can see what happens when seven 11-year-old psychic virgins start acting, breaking the snow-white silence and awakening the avalanche.

Michael: There are hints that this book may not take place in a century-old past, as may seem more obvious, but that it is a look into the future. A possible warning about our coming struggles as humanity, as we wrestle with the ramifications of our systematic destruction of our own planet and existence. Do you see this as a sort of apocalyptic warning, a sort of prophecy? Something more abstract than this? Or do you prefer to let the reader sort these details out on their own?

Hector: Timewise, the book takes place in all eras (including the future). I think that in our culture we have lost the belief (and understanding) in sacrifice as a means for change. I wanted to remind people of that. I have a really bad feeling about the future. On the other hand: the way I read the book, it actually has a happy ending. I believe that in the end of the book [spoiler alert! -> when the seven girls torture themselves to death, this sacrifice actually saves the town and the people in it. <- spoiler alert!] Let me just add that I don’t have an agenda – political or religious – with my work, you might see it as an intellectual preparation for the approaching darkness.

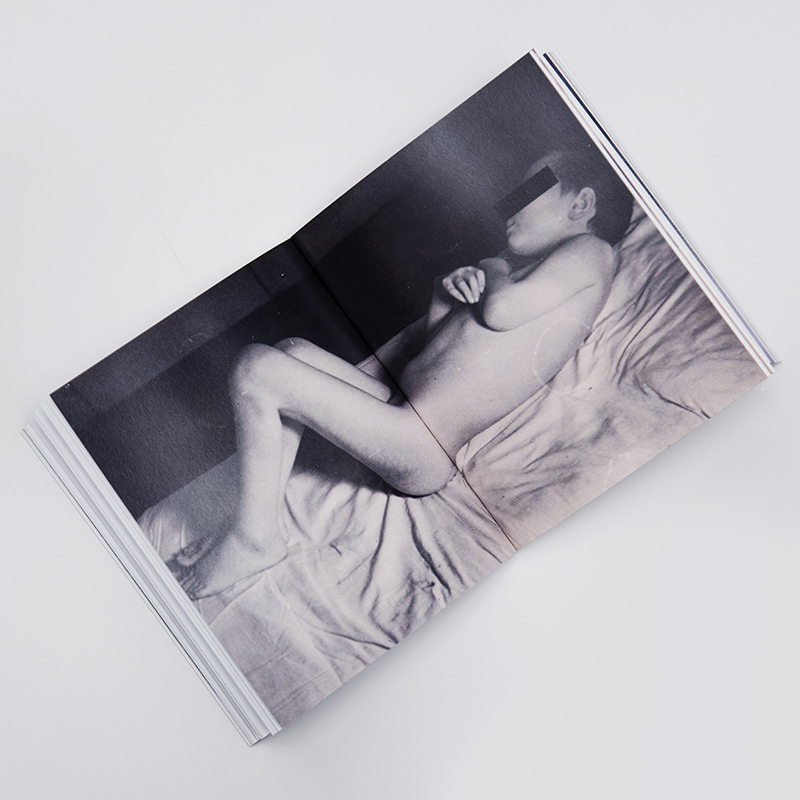

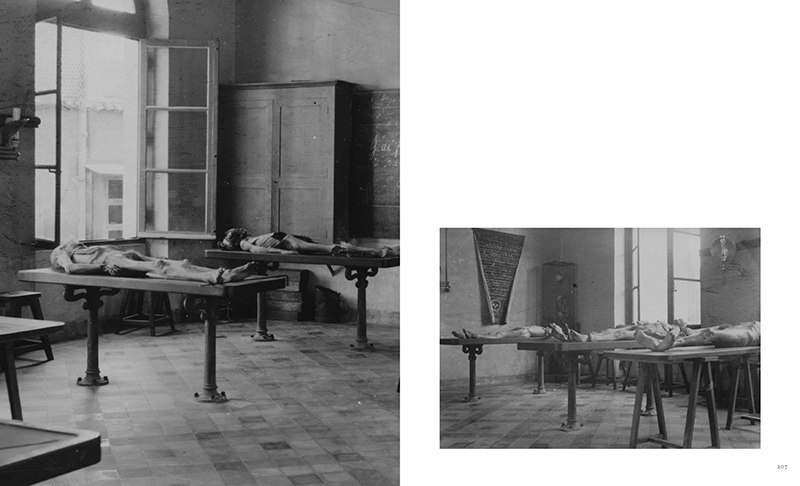

From Three Nails, Four Wounds

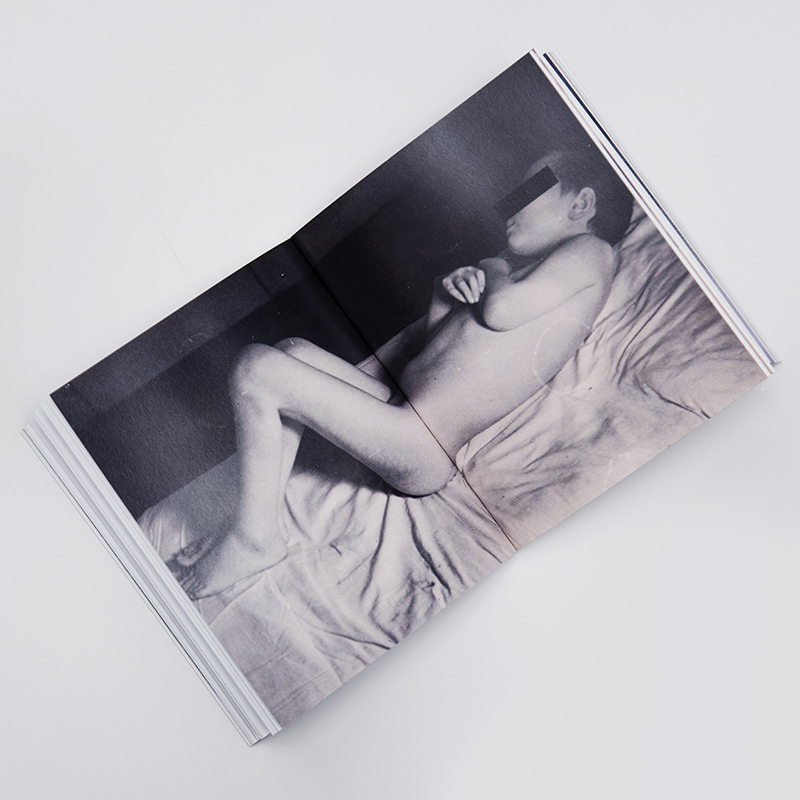

Michael: Were there any worries about the subject matter/visual content of Three Nails, Four Wounds? It is, of course, packed with some quite macabre imagery, unavoidable considering the themes of the photographic content.

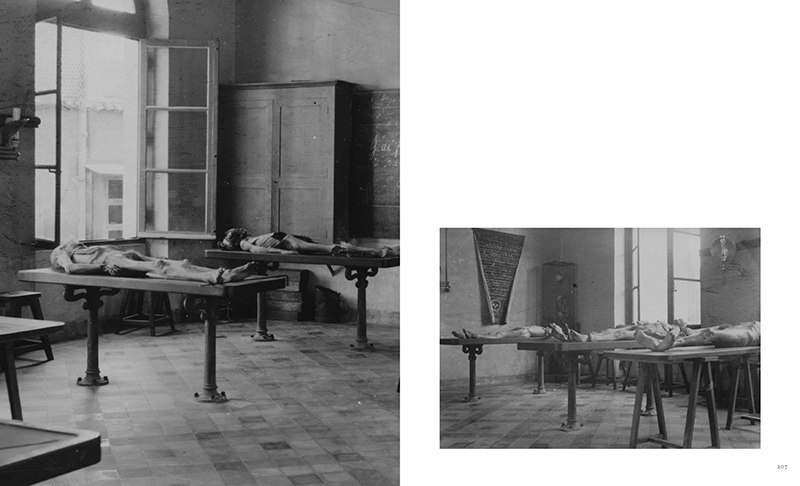

Hector: Not really. I did suggest that we black out the eyes of the disabled children, because those photos were taken in the 1940-50s (so they could still be alive, although I doubt it). It is, of course, a bit weird that photographs taken in the 19th century – for private use or as documentation – are now viewed as art. I see them as historic artifacts worthy of our attention, as memento mori objects, as our past, our collective memory.

From Three Nails, Four Wounds

Michael: It seems reasonably obvious that Infinite Land Press wouldn’t take issue with pressing such an intense release, as it is really the culture of their company. But, what of the hapless consumer that stumbles across your work. The person that had no clue what to expect. Do you have any preferred reaction/emotion you’d like to see coming from them?

Hector: I think the hapless consumer will be alright. If he or she doesn’t like my book they can just throw it away. People get offended by different things, some by photos of the dead, some by naked breasts, some by stupidity. I cannot limit myself by the fears of others. I saw ”The Shining” [Kubrick 1980] when I was ten, and I couldn’t sleep for days. I got extreme anxiety when I had to watch an anti-drug movie in school, where a woman injected heroin into her neck. But I survived – and rather than prosecute the people behind these ”childhood traumas” I feel grateful for being exposed to great art (The Shining) and brutal reality (syringe in neck). And no, I do not have any preferred reactions from a reader – all emotions are welcome.

From Three Nails, Four Wounds

Michael: “The Shining” was the first film that I appreciated more deeply and intuitively. A horror that could overcome the viewer on multiple levels. I, also, wouldn’t have had it any other way. Now that you are moving in the published world, do you have plans for more publications to follow in the foreseeable future?

Hector: I am currently writing a new book. Infinity Land Press is interested. I need at least one more year to finish it. The plan is to get it out in 2020.

Michael: Have you been holding back ideas with the anticipation of coming into your own as a writer, or have you been working through material as it presents itself?

Hector: The latter, I believe. Writing for me is very intuitive. I don’t know what’s going on inside my head when I’m working. It’s a mystery to me – and I like that.

Michael: Martin Bladh mentions that you found inspiration in a passage from the ancient Roman historian Plutarch, in which fear of being carried naked through the market stopped a sudden phenomenon of the Miletus townswomen impulsively hanging themselves. Was this an interesting tidbit you found? Or do you have a deeper fascination with Roman history/stories/mythology?

Hector: I would like to learn more about Roman history, but the Plutarch story was just something that I stumbled upon and felt was connected to my book.

From Three Nails, Four Wounds

Michael: During my studies of Roman history at university, I found the stories: ‘The Golden Ass’ by Apuleius, ‘Satyricon’ by Petronius, and ‘The Satires’ by Juvenal, to all be the most resoundingly interesting. But there is a never-ending torrent of literature worth reading. One must be selective with their time, especially in modernity when vacation and retirement are imaginary concepts for most people. (At least here, in the U.S.)

Hector: I agree, there are so many books to read! Think about a man like Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. He read all books that existed in his time, he possessed all knowledge there was in the world and could grasp the whole intellectual effort made by mankind. You could say that he knew everything. Today that would not be possible – and knowledge is consequently fragmented upon various experts. And now I have contributed to the ever growing pile of books in the world with my own book… I would guess that psychic virgins are very selective readers (or they probably don’t read at all).

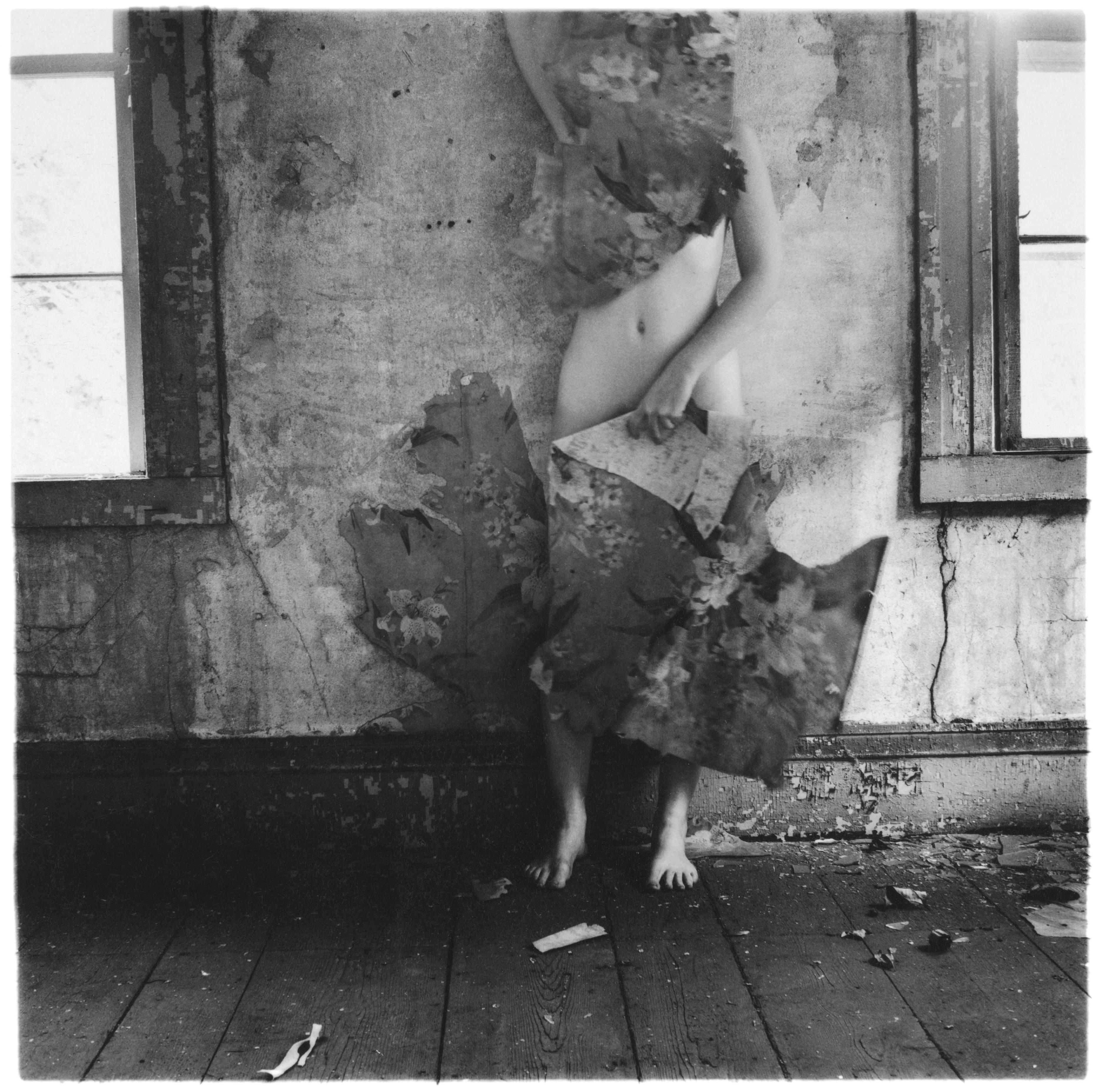

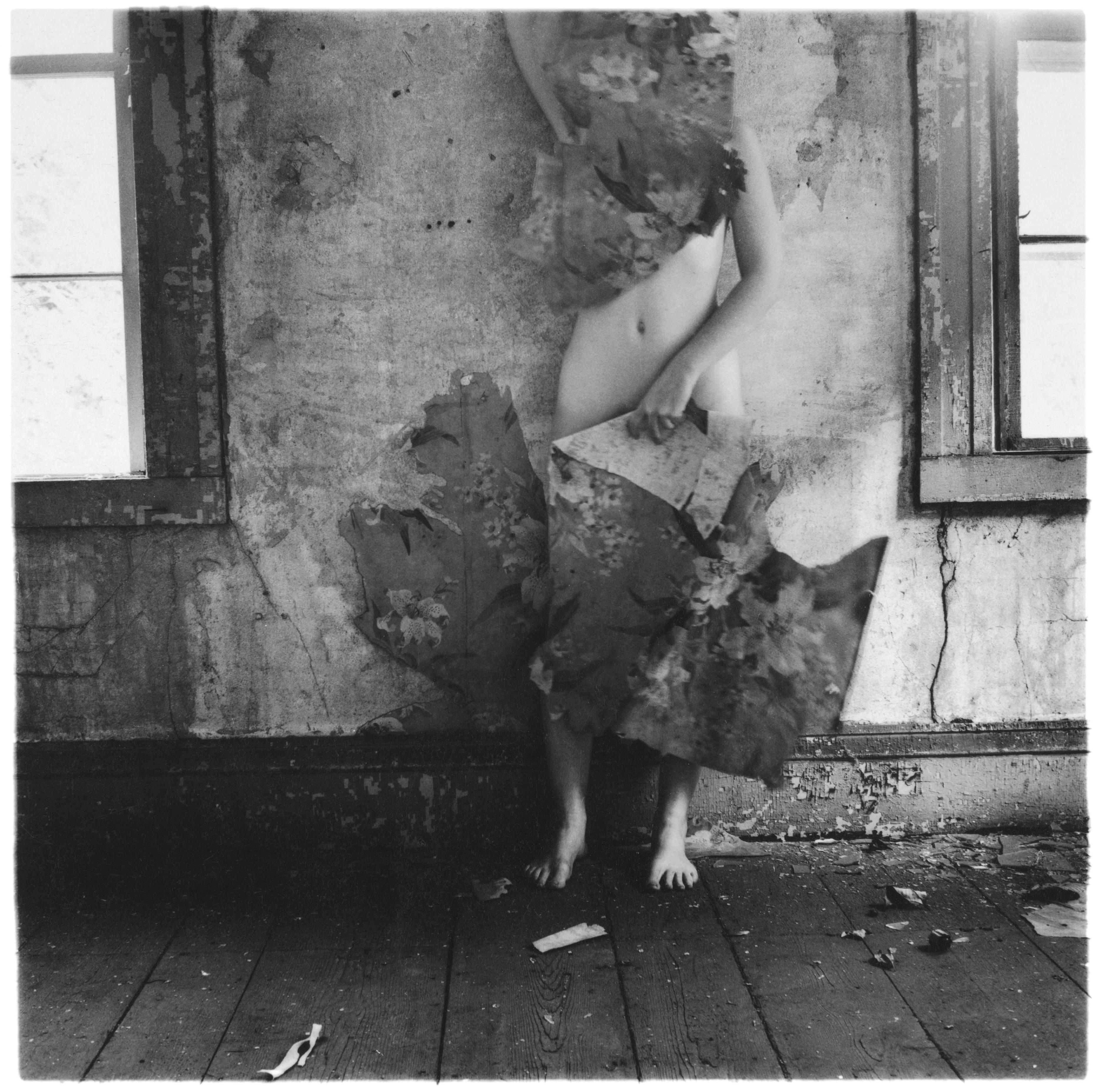

Michael: What are your thoughts on Francesca Woodman’s perspective on her art? Do you think it was auto-biographical in nature? Do you think her still largely unreleased body of work would inform us better on this matter?

Francesca Woodman, Space 2, 1976.

Hector: I was around 20 years old when I discovered Francesca Woodman. It had a great impact on me back then, but I haven’t thought about her for some years now. I don’t want to speculate about her work, if it was auto-biographical or not – it is what it is, for us to enjoy. But there is something mysterious about her, both in her work and her as a person. A feeling of something untold. I saw that documentary [The Woodmans, 2011] a few years ago, it had a weird atmosphere – her father photographing young Francesca-like women, like he was repeating (or continuing) his dead daughter’s work. The documentary didn’t really give much new information, but it was nice to see bits from her performance videos, and to hear her “Minnie Mouse” voice. When she jumped out of a window at her New York apartment she did not leave a suicide note, but in a letter to a friend she wrote: “My life at this point is like very old coffee-cup sediment and I would rather die young leaving various accomplishments, i.e. some work, my friendship with you, some other artefacts intact, instead of pell-mell erasing all of these delicate things.” That tells us quite a bit regarding her aim for perfection. I do hope we will get to see the rest of her work someday, but I wouldn’t count on it.

Michael: Have you found any current photographers that are able to capture her level of emotion in their works which you found so profound with Francesca Woodman?

Hector: For the last ten years or so my focus has been on antique photography, so I’m not really up to date on contemporary artists. But if you want pain, I can recommend the saint-like Spanish photographer David Nebreda.

Michael: Again, in the Afterword, Martin mentions your original fondness for film directors like Pasolini, Dreyer, Bergman and Tarkovsky. Who are some of your more modern favorites? I’m, personally, a huge fan of the works of Lars von Trier and David Lynch, quite a bit above most other current filmmakers, though I’m always looking for some young talents to carry the torch for the next generation.

Hector: When I started writing, film was an important source of influence. I went to a movie theater (that showed classics and art house films) almost every day. But as with contemporary photographs, nowadays I’m not really up-to-date with what’s going on. I like Michael Haneke’s films, Tarr and Alexander Sokurov. If I should name a Swedish director, it would be Ruben Östlund. Sorry, don’t come to me if you want tips on photographers or directors! When I was younger, I searched for influences everywhere, nowadays I try to avoid influences – the thoughts inside my own head are enough.

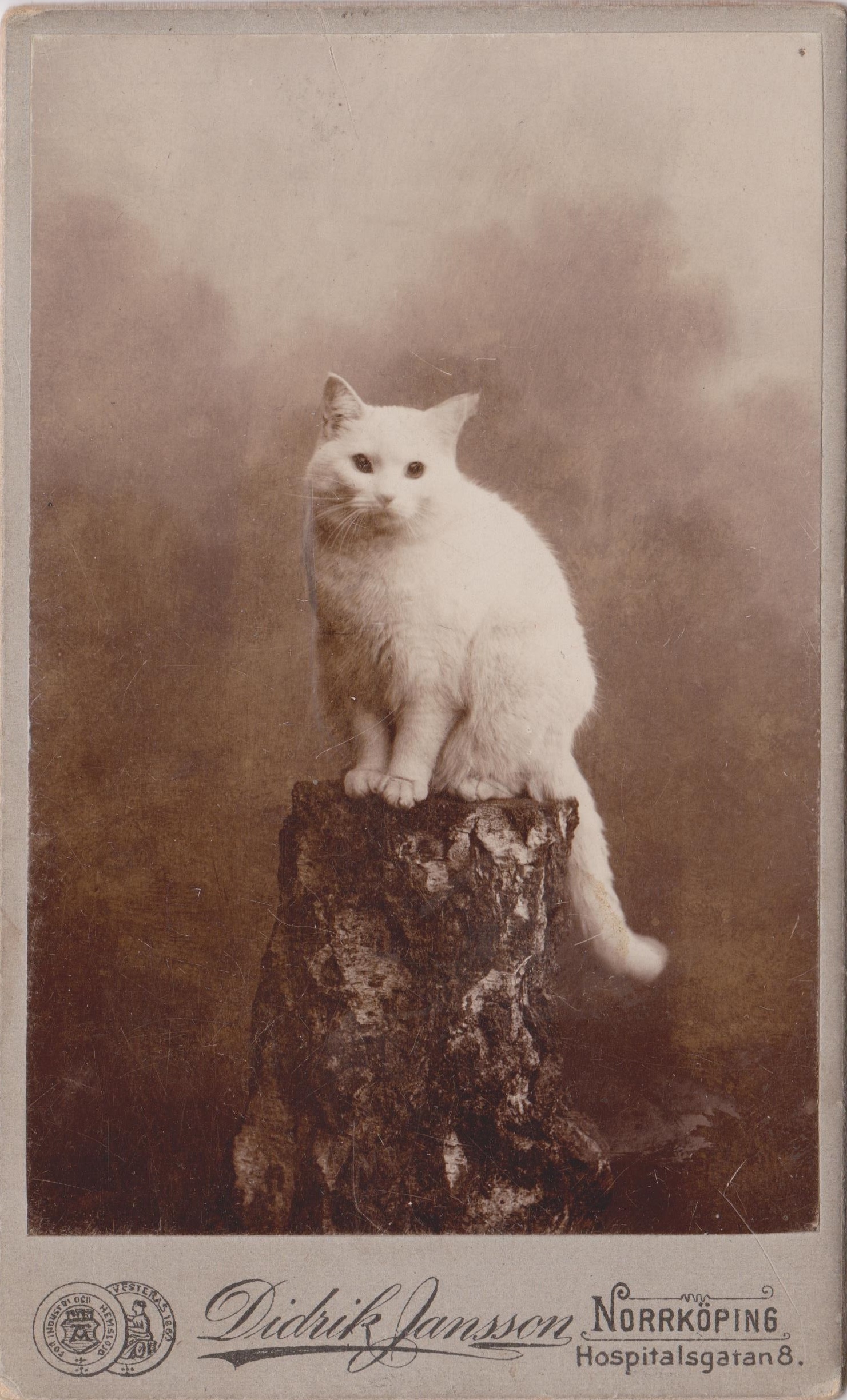

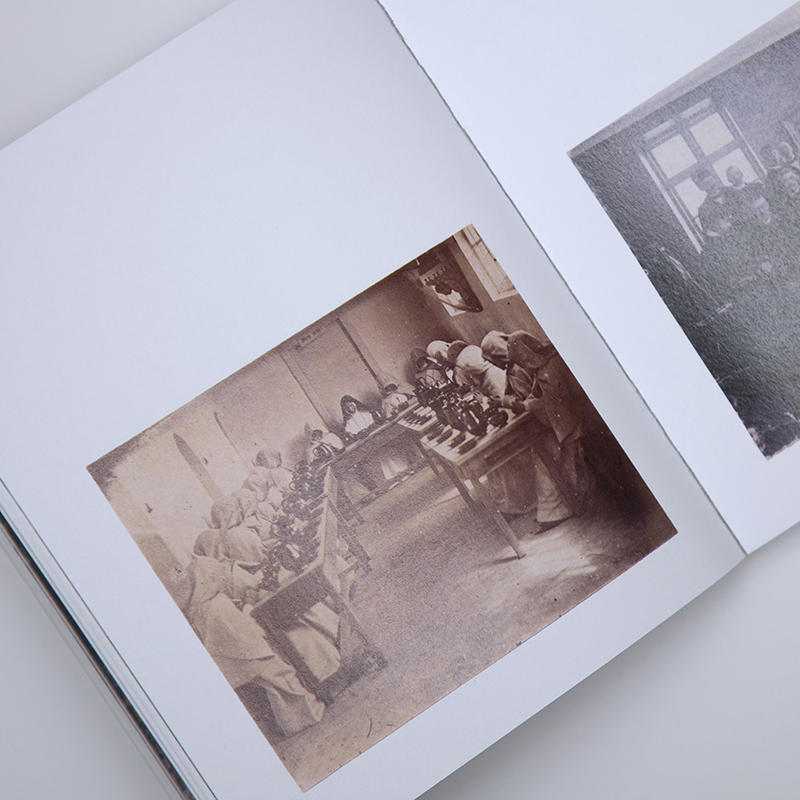

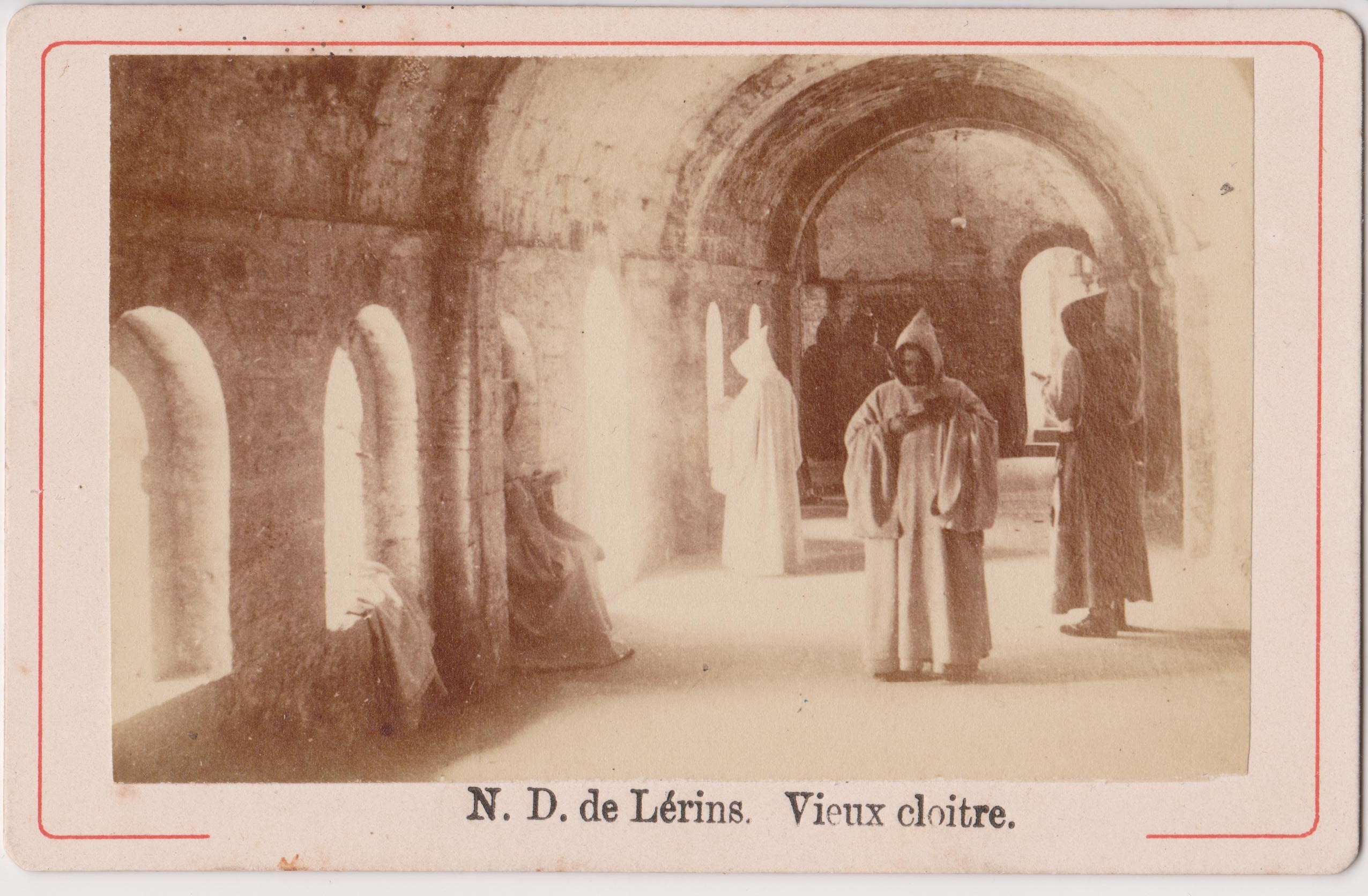

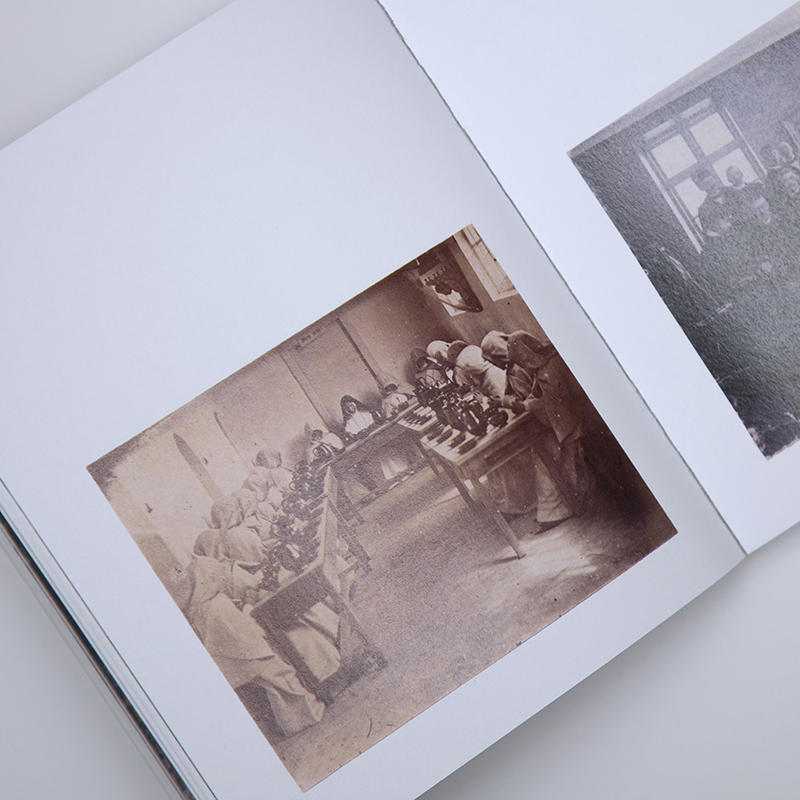

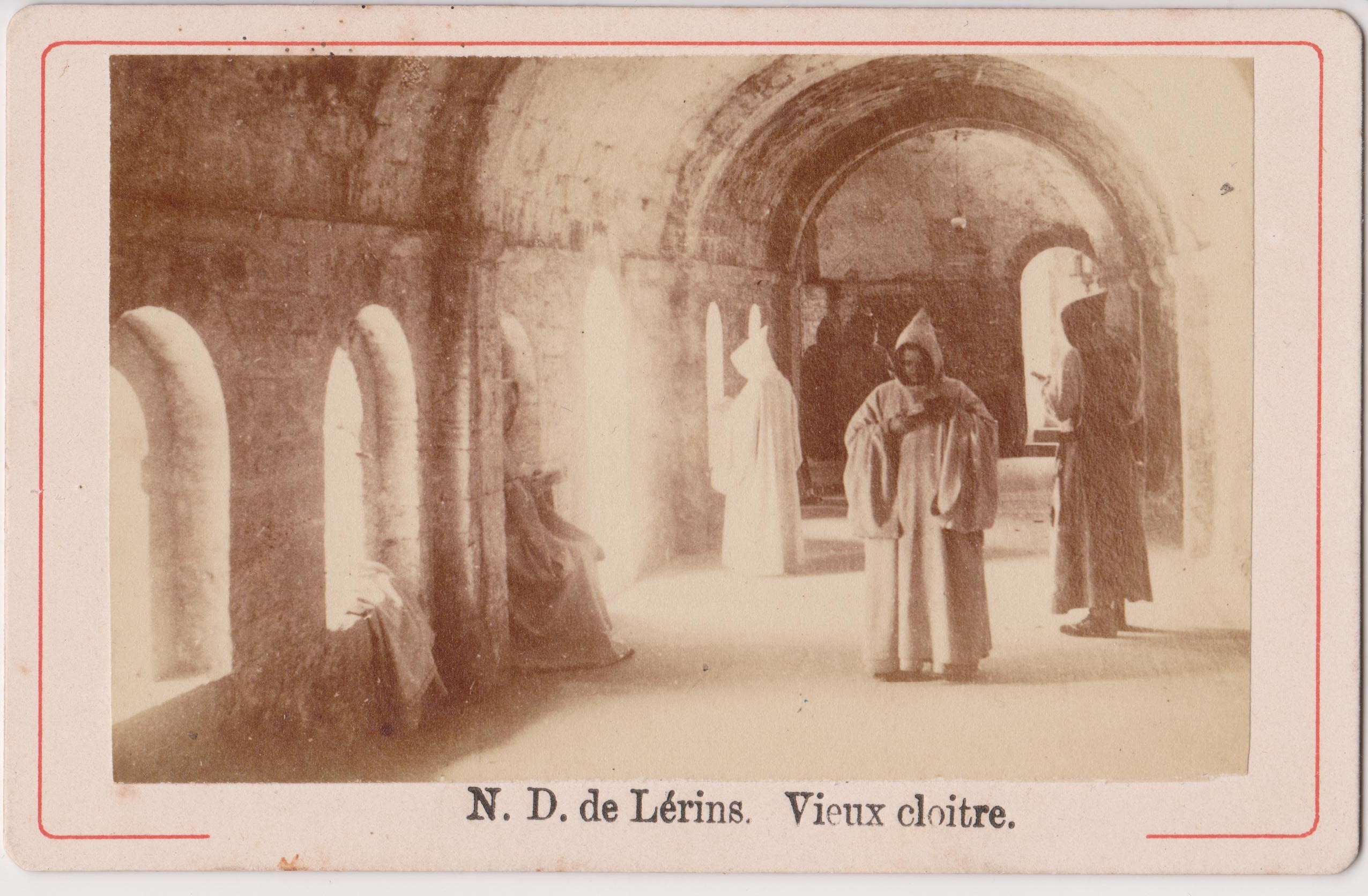

Vintage hidden mother photographs from Three Nails, Four Wounds.

Vintage hidden mother photographs from Three Nails, Four Wounds.

Michael: How has your collection progressed since you started procuring 19th and early 20th century photography? Do you just find this sort of stuff on the internet, or do you attend auctions and other markets for finding such niche photography? I imagine there must be so much of this stuff out there, waiting in attics for some horrified descendant to one day unpack, and they wouldn’t have the slightest clue what to do with an oddity like this.

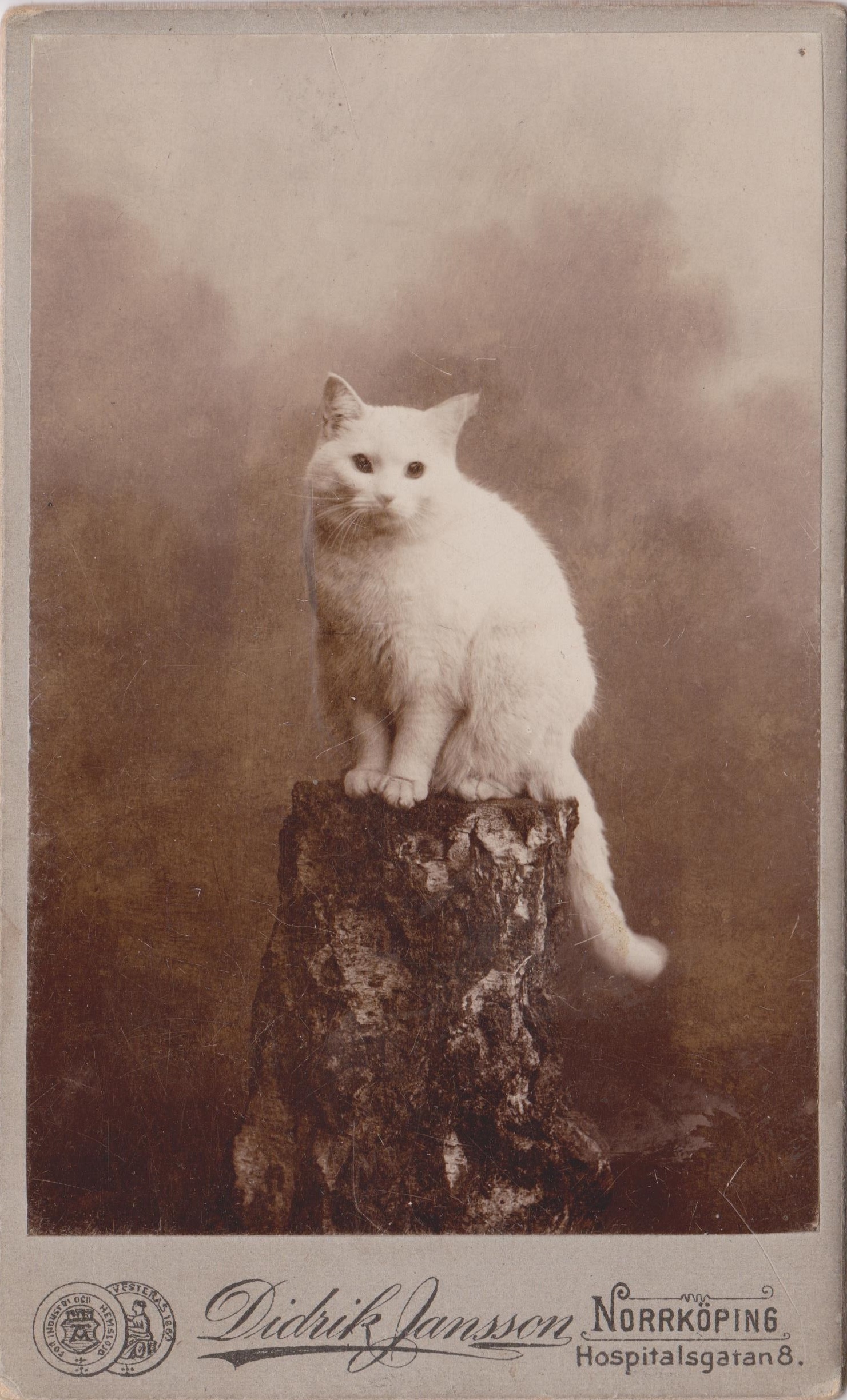

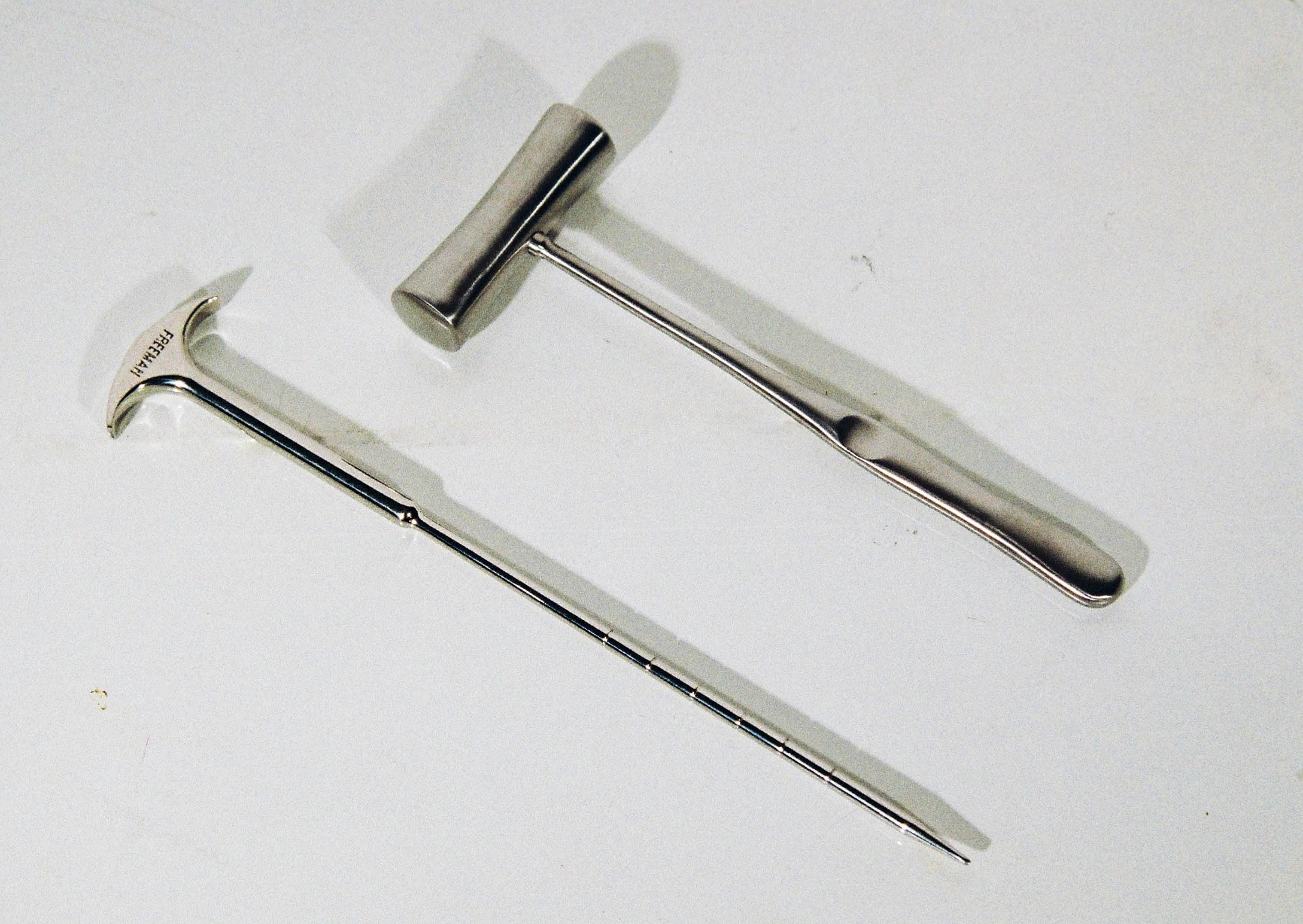

Hector: I think my interest in buying antique photographs started when I saw a “hidden mother” on eBay. I realized that there were a lot of interesting photos on the market. Pretty soon, I started to buy post-mortems, and then medical photos, and then religious themes. Most of them I bought at on-line auctions like eBay, but I have also gotten to know photo collectors from around the world. It’s a small community and we know each other’s interests, we sell and trade with each other. Some of the photos in the book make me uncomfortable too, looking back I think this was a way for me to come to terms with certain fears, and to learn to see beauty even in the nastiest subjects. I like to look at kittens too.

From Meinhof’s personal collection.

Michael: I imagine a hobby like collecting 19th – early 20th century post-mortem photography wouldn’t present itself in a vacuum. Do you have any other interesting collections you’d like to mention?

Hector: Well, that would be old books – but beyond that I don’t really think that I’m such a hoarder. On the other hand, if I had a lot of money, I could easily imagine myself surrounded with exquisite antiques – cylinder music boxes, medieval paintings, large vellum books, talking machines, phonographs, 17th century medical models in ivory, religious objects and relics from saints – in my little castle in the Swiss alps…

Michael: That sounds like a wonderful way of spending a fortune! Has your particular environment had an impact on your artistic direction? As you are Swedish, it is understandable that the works of Ingmar Bergman would come to you at an earlier age than for someone like myself growing up in a rather traditional American family.

Hector: Bergman was important, films like Persona, Hour of the Wolf, Cries and Whispers, had a huge impact on me. Not just visually, but also his treatment of the Swedish language. But most of all, this feeling of independence and freedom; that you can create a piece of art with its own inner logic regarding form and content, not following the manual and not caring about what other people think or say. And, since I have been working with hardcore contemporary art music for my whole adult life, I think (although I cannot explain exactly how) that this has influenced my sense of form and structure. Xenakis, Stockhausen, Cage, Lucier, Ligeti, Sciarrino, Whitehouse…

From Three Nails, Four Wounds

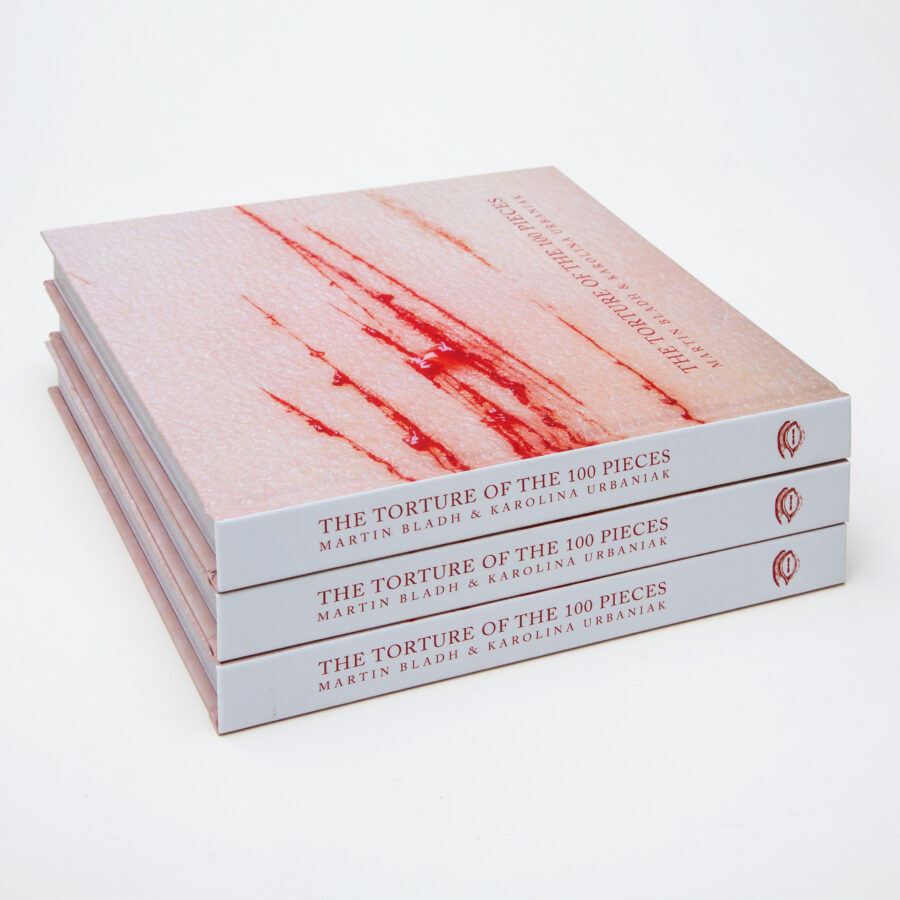

Michael: What are your feelings on Infinity Land Press? Are you happy with the book and Martin and Karolina?

Hector: I had met Martin once before in connection with the recording of the CD Closure… by his post-industrial band IRM. They wanted some additional percussion on the album and, via a mutual friend, I got the job. A few years later when I had finished Three Nails, I heard that Martin had moved to London and started Infinity Land Press, together with Karolina. I sent him the manuscript and he replied like 24 hours later that he wanted to publish it – I was stunned! Martin and Karolina are very professional, both are artists themselves, so we have the same understanding of where the boundaries in our different roles (writer – publisher) should be. I think Karolina’s design of the book is very tasteful and Martin provided a thoughtful afterword that gives the reader some background to the thematic aspects of the book. And of course, the translators Marianne Griolet and John Macmillan were crucial for the birth of this book as a physical object. To produce a book with over 100 photos is expensive, and I wanted it to be affordable (especially since this is my debut), and I think that ILP managed to make a book that feels luxurious without costing a fortune. I am very happy with the result, it’s a little gem. And the reception has been fantastic, I’m humbled by all the praise from my readers.

Michael: I think you hit your goal nicely. I forgot the book was under £20, it certainly feels like a more expensive and very well-made product. Do you see any other publisher out there working on projects of these sorts?

Hector: I think you know more about publishers than I do, Michael. But we have, for example, Kiddiepunk [Michael Salerno], and Amphetamine Sulphate [Philip Best]. I was happy that Wakefield Press released two books by Gabrielle Wittkop a few years ago.

Michael: I am learning new things every day. I am constantly finding new artists, publishers, film directors, that are changing my ideas on art and its limits. I just try to bring the zine’s readers along in my process of discovery. You never know where the next hidden gem will decide to shine and reveal itself. I find that an artist’s particular set of interests can often unlock a whole new world of interests to their followers. So, I thank you for sharing some insight, not only into your own work and process, but also into the things that brought you to become the artist you are today. I thank you again for your time, and I’ll leave the final words to you!

Hector: The pleasure was mine, Michael. Thank you for spreading the New Gospel! My final words… well, the aborted calf is shaved and skinned. The skin is stretched over the firmament: In the afternoon sun, people cease to cast shadows. In the town square, the puppet theater closes for the day. The puppet master pulls off the puppets and discovers that his hands are soaked with blood. You see, this is for real.

Purchase Three Nails, Four Wounds here.

Hector Meinhof Links

Official Website

Facebook

Instagram

Youtube

Hidden Mothers band site

Like this:

Like Loading...

Vintage hidden mother photographs from Three Nails, Four Wounds.

Vintage hidden mother photographs from Three Nails, Four Wounds.